That said, Ill take my fantasy city any day.

That said, Ill take my fantasy city any day.

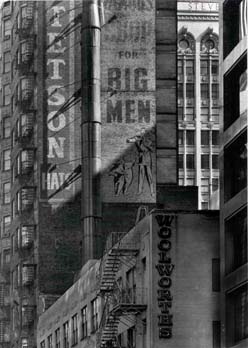

In my mind there are two Chicago Loops, the one seen through a child's eyes, filtered through many years of memory, and the Loop of history. The city of memory is a fantasy, a perfect city where majestic buildings cast their long shadows on the street, people come and go, busses and cars jostle for position while the el rumbles overhead. There are

the great department stores, the restaurants, nightclubs and theaters, busy day and night, drawing people from all over the city. Signs lit by flashing lights advertise everything from gasoline to suntan lotion to the latest news.

In my mind there are two Chicago Loops, the one seen through a child's eyes, filtered through many years of memory, and the Loop of history. The city of memory is a fantasy, a perfect city where majestic buildings cast their long shadows on the street, people come and go, busses and cars jostle for position while the el rumbles overhead. There are

the great department stores, the restaurants, nightclubs and theaters, busy day and night, drawing people from all over the city. Signs lit by flashing lights advertise everything from gasoline to suntan lotion to the latest news.

Workers hurry to work in the morning then back home again at night through the doors of the great railway stations, as long distance passengers sit in magnificent waiting rooms before boarding trains with evicative names like The Empire Builder, The Twentieth Century Limited or The Super Chief. It is a place of endless energy and fascination, where every turn brings a new discovery. It is a city of architecture, of "democratic" principles of design and big plans, the home of the Chicago School.

My concept of what a city should be was formed by the Loop. I will forever associate the sights, sounds and smells of downtown Chicago in the 1960s with the idea of "The City". A sign from my childhood at the Western Avenue el stop said it all. When a Loop-bound train approached the station, the sign flashed simply:

If I had the opportunity to design a city, it would be modeled after the Chicago Loop of my memory.

The historic Loop is a different story.

Chicago was not built out of a philanthropic spirit, but an entrepanurial fervor.

From the beginning this was a place where people came to make a fast buck.

City boosters may now rave on and on about our great architecture. Idealists think of our landmark buildings as monuments, as artifacts to be preserved forever. Forgotten is the spirit in which buildings get built. We brag that Chicago is the birthplace of the skyscraper. But skyscrapers weren't invented to be works of art, they were invented in order to cram as many people into as small a space as possible. Some of the architects who made this possible did their work with grace and skill, and happened to create an art form in the process. But until very recently, as soon as a building was no longer considered commercially viable, commerce won over art every time. And there were plenty of architect "artists" ready to build over the ruins of last year's monument. The forces that created the great buildings also destroyed them.

That said, Ill take my fantasy city any day.

That said, Ill take my fantasy city any day.

As a child, I was fortunate to spend at least one day a week downtown, sometimes two. It was during the early to mid 1960's, just about the time when as a friend recently remarked, "everything just went to hell."

Needless to say, the Loop has changed drastically in the past thirty odd years. When I was a kid, there were six major department stores on State Street, the Loop had about ten palatial movie theaters, several rail terminals and major hotels, and hundreds of storefront shops. The Loop was a self contained world. One could live, work, shop, and be entertained downtown without ever having to leave its boundaries.

The department stores then really had departments, they were not just big clothing stores. Marshall Fields had a music shop where you could buy not only records, LPs of course, but sheet music and pianos as well. They devoted half a floor to books, another large area to fabrics, and another to appliances.

But most important of all was the toy department, it was easily the best toy store in the city. Half of the fourth floor was devoted exclusively to toys. There were magnificent model train layouts, Lego Block villages, and giant Erector Set constructions. Lots of doll stuff too I suppose but that of course was irrelevant to me.

To this day, the very words, "The Fourth Floor of Fields" resonate with magic in my ears.

Every Saturday my mother and I would end up on the fourth floor, she would buy me a toy car. One could say that there was a direct pipeline between that store and my bedroom.

Every Saturday my mother and I would end up on the fourth floor, she would buy me a toy car. One could say that there was a direct pipeline between that store and my bedroom.

I particularly remember a gregarious middle aged man who worked the magic counter. God knows how long he worked there. With great pinnache he gleefully demonstrated all the magic tricks they had for sale. Eventually the store gave up the magic counter and once relegated to selling teddy bears, much of his joy seemed to be snuffed out.

The pinnacle of Chicago department stores, Marshall Fields was my mother's domain, she wouldn't set foot in any other store on State Street. My grandmother on the other hand, only went to Fields for the boxes bearing the store's name in which she would wrap the presents she bought at Goldblatts.

Physically and symbolically located on the other end of State Street, Golblatts represented the opposite end of the socio-economic spectrum from Marshall Fields. Goldblatts was a major presence in all of the neighborhood shopping districts throughout Chicago. Catering to the working man and woman, their stores, or as my mother called them, "junkshops", were usually housed in ornate terra-cotta buildings. I particularly remember Goldblatts' elevators which back then were hand operated by very crabby old women. The flagship store downtown was similar to the neighborhood stores, only magnified in size by ten. Contrary to the magnificent exterior, the store was a no-nonsense establishment that sold low cost yet reliable merchandise. Yet unlike the Walmarts and Targets of today, Goldblatts still had the feeling of being someplace special, just like its haughtier neighbors to the north. When I was old enough to go Christmas shopping by myself, I went to Goldblatts to buy an Elgin watch for my mother, costume jewelry for my grandmother, and six packs of after shave, Mennen for my father and Aqua Velva for my surrogate grandfather Mr. Willie.

Shopping in the Loop was not limited to department stores. The storefronts boasted various establishments like grocery stores, stamp and coin dealers, photo and hobby shops, and hardware stores to mane but a few.

Kroch's and Brentano's had their flagship store on Wabash Avenue. It was a huge bookstore that did not sell coffee. Kroch's took up two huge floors and a mezzanine. Every time I developed a new interest, I could count on Kroch's to supply the book or magazine to satisfy my curiosity. Of special interest was a walled off room in the art depertment which was devoted entirely to books on photography. It was nicknamed "the saints and sinners corner" and run for years by an elfish man named Henry Tabor who incidentally, gave me my first one man show on the walls of the store. Big as it was, Kroch's paled in size to today's chain book stores. Faced with competition from the big chains, as well as threats of employees organizing, the store shut its doors and left the Loop without a decent bookstore until the recent opening of a major chain store on State Street.

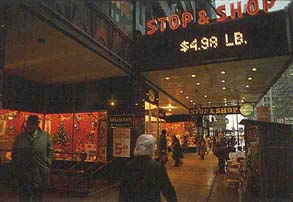

Then there was Stop and Shop. This was a magnificent old world food market where one could buy any number of foodstuffs whose mere caloric and fat content would today necessitate the posting of warning labels as you enter the store. I never saw anything like it outside of Europe. Entering the store took you into a completely different world. Here one could find all the necessities for the perfect 19th Century epicurean life. Best of all was the smell, which was the combination of several decades worth of spices, meats, and cheeses lingering in the air. One day sadly, Shop and Shop just disappeared. It had become another genteel anachronism in the Loop

of the late 1970's which by that time became dominated by fast food joints, wig shops and empty store fronts.

Then there was Stop and Shop. This was a magnificent old world food market where one could buy any number of foodstuffs whose mere caloric and fat content would today necessitate the posting of warning labels as you enter the store. I never saw anything like it outside of Europe. Entering the store took you into a completely different world. Here one could find all the necessities for the perfect 19th Century epicurean life. Best of all was the smell, which was the combination of several decades worth of spices, meats, and cheeses lingering in the air. One day sadly, Shop and Shop just disappeared. It had become another genteel anachronism in the Loop

of the late 1970's which by that time became dominated by fast food joints, wig shops and empty store fronts.

I'm not the best to judge the culinary standards of Downtown restaurants in the sixties, even though I ate at many of them. A perfect meal for me in my childhood consisted of three things, a hamburger, french fries, and chocolate milk. Nowhere could I find a better combination of the three than at the chain Wimpys. The burgers were flat, just the way I liked them, the fries, extra greasy, and the shakes were thick. My mother's more sophisticated tastes prevented us from eating there often but every once and a while she gave in.

On our Saturday jaunts, my mother occasionally took me to a restaurant specializing in doughnuts called the Mayflower. Displayed in the front window was a doughnut machine where conveyor belts would move the dough from the mixing tub, to the cauldron of boiling fat, then onto trays for the toppings. Mounted on an inside wall was the restaurant's symbol, a large image of two men in medieval garb standing on either side of a shield. One man held a fat doughnut and boasted a broad smile. The other man held a thin doughnut and frowned. On the shield was written the restauant's mission statement:

Whatever be your Goal,

Keep your Eye upon the Doughnut,

And not upon the Hole!"

Special occasions would find us at the Blackhawk on Wabash, where they had the thick burgers that I didn't like, or at the Chicago institution The Berghoff, which briefly had a restaurant on Wabash. The place that I considered to be the coolest restaurant in the world, was The Well of the Sea, in the basement of the Sherman House Hotel. The restaurant was very dark, most of the illumination was from ambient light coming from deep aquamarine lights along the walls on which were displayed sea related items, nets, hooks, anchors, etc. All of the servers were black men who dressed in white waistcoats. The service was impeccable. I remember eating there one New Years Eve when my parents were out at a party with friends. We later witnessed the official countdown to 1967 on the big flashing light sign at State and Randolph and then got home in time to catch an Astaire-Rodgers movie on TV. To an eight year old, it was the height of sophistication.

To me one of the joys of any city are the little things that take you by surprize. THe Loop once had many off-beat establishments that you entered by

descending stairs directly from the street. South Pacific Polynesian

restaurant on Randolph was one. The RR Ranch was another. To lure

customers down the stairs, these places had to make their

presence known. The South Pacific had a wonderful neon sign complete with

palm trees. The Ranch was a Loop classic, as out of place Downtown as Stop

& Shop became, it was a bar and restaurant with a country/western theme

that featured a band called the Sundowners. A publicity photograph of the

band graced the entrance. Upon seeing the Sundowners on stage it became

quite obvious that the photograph had been around the block about as many

times as the band.

To me one of the joys of any city are the little things that take you by surprize. THe Loop once had many off-beat establishments that you entered by

descending stairs directly from the street. South Pacific Polynesian

restaurant on Randolph was one. The RR Ranch was another. To lure

customers down the stairs, these places had to make their

presence known. The South Pacific had a wonderful neon sign complete with

palm trees. The Ranch was a Loop classic, as out of place Downtown as Stop

& Shop became, it was a bar and restaurant with a country/western theme

that featured a band called the Sundowners. A publicity photograph of the

band graced the entrance. Upon seeing the Sundowners on stage it became

quite obvious that the photograph had been around the block about as many

times as the band.

The tremendous variety and unexpected nuances contributed to the joy of wandering through the Loop, quite the contrast to recent office buildings with their sterile plazas and cold lobbies. One of the more incongruous buildings of the old Loop which is still around today, is St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church on Madison Street. The church is stark, it has a highly polished pink marble facade with foreboding brass doors. There are no windows to speak of. The most distinguishing feature of the church is its three story likeness of Christ on the Cross gazing down at the passersby on Madison Street. I would occasionally find myself downtown with my grandmother and we would enter the church for her to say some prayers and light a few votive candles, (which at this particular church were little electric lamps shaped like candles). I always felt uncomfortable in St. Peter's, it was so cold and foreboding that I could directly feel God's impending wrath. There was even a peculiar smell inside which I always associated with the church. Later I found out that the smell did not come from anything of a sacramental nature, but from a particular brand of floor wax. Still to this day, whenever I encounter the smell of that wax, I feel compelled to genuflect.

While a church was a rare sight in the Loop, the temples to entertainment were plentiful.

At nighttime, the streets of the North Loop were bathed in light from the

theater marquees. Up until the late seventies, movies all had their first run

in one of the big Loop theaters. I remember going to movies typically not on

weekends but on school holidays. Those were special days when my mother would

drive her 1965 Mustang to the Loop, and park in one of the attendant lots. We would

probably do a little shopping at the artist supply store Flax, go to Marshall Fields,

then head off to the Chicago, State and Lake, or United Artists theaters for

a film. The McVickers Theater on Madison Street had live theater and it was

there we saw a production of Fiddler on the Roof, my first experience of live theater.

The Clark Theatre was a revival house and I remember going there

to see all four Beatles movies in one sitting, with my grandmother!

The Michael Todd Theater had the kiddie fair, one birthday was spent

there with a bunch of friends seeing Dr. Doolittle. Ironically, next door was the theater's

twin, the Cinestage,

that showed exclusively "adult" movies. The Bismark Theater

in the hotel of the same name usually showed the big budget movies. Next door to it

was the wonderful Cafe Vienna.

While a church was a rare sight in the Loop, the temples to entertainment were plentiful.

At nighttime, the streets of the North Loop were bathed in light from the

theater marquees. Up until the late seventies, movies all had their first run

in one of the big Loop theaters. I remember going to movies typically not on

weekends but on school holidays. Those were special days when my mother would

drive her 1965 Mustang to the Loop, and park in one of the attendant lots. We would

probably do a little shopping at the artist supply store Flax, go to Marshall Fields,

then head off to the Chicago, State and Lake, or United Artists theaters for

a film. The McVickers Theater on Madison Street had live theater and it was

there we saw a production of Fiddler on the Roof, my first experience of live theater.

The Clark Theatre was a revival house and I remember going there

to see all four Beatles movies in one sitting, with my grandmother!

The Michael Todd Theater had the kiddie fair, one birthday was spent

there with a bunch of friends seeing Dr. Doolittle. Ironically, next door was the theater's

twin, the Cinestage,

that showed exclusively "adult" movies. The Bismark Theater

in the hotel of the same name usually showed the big budget movies. Next door to it

was the wonderful Cafe Vienna.

The places I miss the most in the Loop are undoubtedly the railroad stations. As the hub of the nation's railway system, Chicago naturally had magnificent monuments to the railroad. Since the city fathers and rail magnates could not successfully cooperate to create a unified system of tracks leading to one station, we ended up with six of them.

The headhouse of Northwestern Station stood at Madison Street between Canal and Clinton Streets. At one time the station served the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad's long distance routes. However I only remember it as a commuter station which gave it a more businesslike atmosphere that the more cosmopolitan Union Station three blocks to the south.

Men in suits grabbing a quick cocktail before rushing to catch their train for home, and gamblers in fedoras sneaking away from work headed for the track were the principal occupants of the station. Advertisers, knowing their market boasted: "Forbes; Capitalist Tool" on the billboards. It was the epitome of the corporate lifestyle, the mystery existence that went on inside those downtown towers I loved so much. It was the kind of life that fascinated but never claimed me. I always associate this station with my grandmother who in her younger days must have taken the C&NW's 400 up to Milwaukee. She and I would go there to look around and stop in one of the restaurants or bars where she would have a high ball, her drink of choice.

The greatest of the Chicago rail terminals was Union Station. A result of a failed attempt to unify all the rail lines originating in Chicago, Union became the biggest and most important of all of Chicago's rail terminals.

It was the concourse that was the real hilight of the complex. The concourse was a separate building across Canal Street from the headhouse. Ironwork inspired by New York's Pennsylvania Station made for a tremendous play of light from the sunlight coming in through the clearstory windows. This was perhaps Chicago's most spectacular interior. It was fitting since the concourse was the first sight people many had of Chicago after disembarking from their trains and the last thing they saw before they got on a train pulling away from the city.

Sometimes on long Sunday afternoons, my grandmother, Mr. Willie and I

would go to Union Station, grab a bite at Fred Harvey's, (another

restaurant suited to an eight year old's taste) and sit and watch the

world pass by. Once in a while we would take the commuter trains to the

end of the line, spend a few hours in Aurora or Elgin, and come back to

the beautiful concourse, making a grand entrance as if we had just crossed

the continent. Once a year we would take Milwaukee Road's Hiawatha up to

Milwaukee. For many years this was my regular summer vacation. The most

distinguishing feature of the Hiawatha was the beautiful observation car at

the rear of the train which ended in an elliptical dome . The name of the

train was proudly written in script on a stainless steel band which wrapped

around the back of the observation car.

Sometimes on long Sunday afternoons, my grandmother, Mr. Willie and I

would go to Union Station, grab a bite at Fred Harvey's, (another

restaurant suited to an eight year old's taste) and sit and watch the

world pass by. Once in a while we would take the commuter trains to the

end of the line, spend a few hours in Aurora or Elgin, and come back to

the beautiful concourse, making a grand entrance as if we had just crossed

the continent. Once a year we would take Milwaukee Road's Hiawatha up to

Milwaukee. For many years this was my regular summer vacation. The most

distinguishing feature of the Hiawatha was the beautiful observation car at

the rear of the train which ended in an elliptical dome . The name of the

train was proudly written in script on a stainless steel band which wrapped

around the back of the observation car.

As a child I had no clue that so many of the things that I loved about the Loop would soon fade into memory. One by one, a store here, a theater there would disappear. Great plans were made, buildings were torn down, the plans fell through leaving gigantic holes in the ground. Where new buildings were built, architects planned for plazas and setbacks, which brought space and sunlight back to the street but also killed off much of the intensity, density, and intimacy that made downtown such a vibrant place. The once active street life in the Loop has been significantly reduced. The railroads who couldn't get out of the passenger business quick enough, were succeeded by Amtrack who kept alive, but also homogenized train travel. Of the six proud rail stations, only the headhouse of Union Station and an unrecognizable Dearborn Street Station remain. Marshall Fields was purchased by an out of town corporation that has proven to have little regard for their employees or for the company's tradition of being Chicago's pre-eminent store. They even got out of the toy business!

I couldn't have realized how lucky I was to have experienced the Loop during the final moments of its heyday when it was really something.

Driving into the Loop the other evening, I looked at the lights coming from the skyscrapers and noticed that practically all the buildings visible from the expressway were built since I fell in love with this city. "My God...", I thought; "...there's a whole new city there that I never knew as a child". From within, the Loop may resemble Houston more than the Emerald City but from a distance the city looks more like Oz than ever before. And whenever I see children gazing up in awe at the El, I realize that my perfect city is not merely a faded memory.